Fault Tolerant

Introduction

In the real world, servers are prone to failures. Especially in distributed systems, maintaning the balance among performance, consistency, and fault tolerant is a continuous challenge.

In Lab 1 Map Reduce, we focused on leveraging concurrency to improve performance. In Lab 2 Key Value Server, we designed a strongly consistent key/value system. Now it is time to turn our attention to fail-stop faults and the design choices required to improve server-side fault tolerant and achieve high availability.

Before proceeding, it is highly advisable to read the paper "Fault Tolerant Virtual Machine".

Replication

Replication is one of the simplest and most common ways to achieve fault tolerance. There are two common approaches to replication:

- State Transfer — sending the entire state of the primary to the backup.

- Replicated State Machine (RSM) — sending operations or external events so that all replicas perform the same deterministic steps.

The paper provides an in-depth examination of the Replicated State Machine approach. The key observation in this system is that most services we want to replicate behave deterministically except when they receive external inputs.

And this assumption is exactly the hardest part in practice — even tiny nondeterministic differences, such as floating-point operations, physics calculations, or retrieving the current time, can quickly desynchronize replicas.

The standard solution to this problem is to let the primary execute all instructions and stream the resulting outputs to the backup. The backup does not execute instructions itself; instead, whenever it reaches a point where it would normally perform an operation, it simply waits for the primary to provide the correct result.

You may have noticed that the paper explicitly limits its design to uniprocessor environments. It does not attempt to extend the virtual mechanism to multi-core or parallel execution. The reason is straightforward: once multi-core CPUs execute instructions concurrently, the interleaving of those instructions becomes nondeterministic, making deterministic replay extremely difficult to achieve in practice.

VMware later introduced a replication system that does support multi-core virtual machines. However it is more relies on state transfer ranther than RSM. In practice, state transfer turns out to be far more robust when dealing with multi-core and parallel workloads, since it avoids the need to reproduce the exact instruction interleavings that occur on a real multi-core CPU.

VMware Fault Tolerant

When discussing fault tolerance and replication, it is helpful to keep serveral core questions in mind:

- What level of state needs to be replicate?

- How closely synchronized must the primary and backup remain?

- What is the mechanism for switching between primary and backup?

- How should anomalies during the cutover be handled?

- How is replication re-established after a failover?

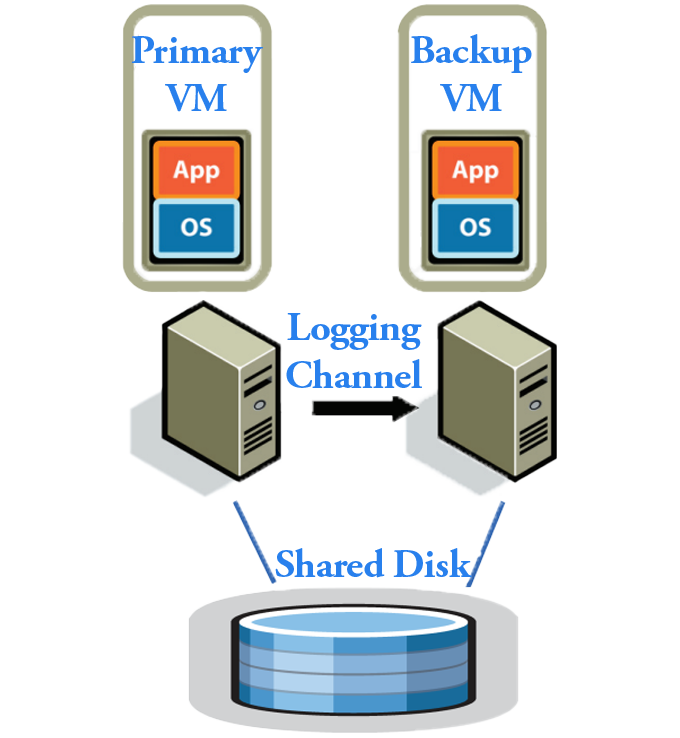

VMware Fault Tolerance replicates the entire machine state, as illustrated in the figure below. Although this approach operates below the application level—and may therefore be less efficient—it is significantly more general and transparent to applications.

Logging Channel

In this model, the primary and backup communicate through a network stream referred to as the Logging Channel.

The most import things we're worried about inside the Logging Channel is those Non-determinstic events:

- Clients Inputs-packet (data + interrupts)

- Nondeterministic instructions such as random number generation, floating-point operations, physics calculations, or reading the current time

Multi-core and Parallel execution

Since the Logging Channel is the only communication path between the primary and backup, the primary election mechanism also operates through it.

In this design, if the backup fails to receive data from the Logging Channel for a certain period, it will "Goes Live": it stops waiting for further logged events, the virtual machine monitor allows it to execute freely, and it begins producing its own outputs—effectively becoming the new primary.

There are absoluly many details inside the Logging Channel. For illustration, Log Entry may describe with go type like below.

type LogEntry struct{

//the number of instructions since the machine booted

//The backup executes until reaching this instruction index,

//at which point the VMMonitor intercepts execution

//and supplies the logged result.

//This requires hardware support.

uint64 InstructionNumber

//define which type of Non-determinstic events.

interface Type

//for packet, data will just be the packet data

//for those werid instructions, it will be the rusult of

//the instruction when it was executed on the primary.

string data

}Thanks to the instruction number, the backup's virtual machine monitor maintains a buffer of pending events that have arrived. It prevents the backup from executing beyond the instruction count of the most recent buffered event. As a result, the backup can never "run ahead" of the primary.

Consider that when a client issues a request that modifies server state, a subtle problem can occur if the primary crashes immediately after generating the ouput but before the backup has received the log. Due to network delay or a missed logging message.

The backup may not have the most recent state. If the backup then takes over as the new primary, it will serve subsequent client request based on the stale information, potentially leading to incorrect or inconsistent results.

To address this, the paper introduces the "output rule" the primary’s VMM must not release any output to the client until the update has been sync and acknowledged by the backup through the logging channel. This ensures that no client ever observes a state that has not yet been safely replicated.

This requirement also highlights an inherent trade-off. Keeping the primary and backup as closely synchronized as possible is essential for strong fault tolerance, yet waiting for logging acknowledgment inevitably adds latency to the primary’s response time. Managing this balance between consistency and performance is the fundamental motivation behind the different replication strategies discussed in the system.

Split-brain disaster

There is still one dangerous scenario: both the primary and the backup may be alive, both serving clients, but unable to communicate with each other through the logging channel. When this happens, each VM may incorrectly conclude that the other has failed and that it should become the primary.

To prevent this, the system requires a third-party arbitrator that both replicas can consult to decide which one is allowed to act as the primary.

In this figure model, the shared disk serves as this arbitrator. The VMs use a small piece of metadata, implemted as "test-and-set" falg to perform a locking operation. Only the machine that successfully acquires this lock is permitted to run as the primary, while the other must remain in backup mode or shut down its execution.

Of course, this design implicitly assumes that the shared disk itself is highly available. In practice, the shared disk must also be backed by a reliable, replicated storage system; otherwise, it would become a single point of failure.

mimizh

mimizh